With a 98 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, an Academy Award under its wing, and being a total box office success, it's hard to say Boyhood isn't a win for independent movies everywhere. Yet, the choice for director Richard Linklater, known for his altercations of time and personal relationships, to film this over the course of 12 years is undoubtedly impressive to a wide audience. As a coming-of-age film, to be different in the theme of "growing up" can be difficult, but Linklater set to convey the human experience through the means of unconventional editing and scene cuts, which may not be seen in average coming-of-age film.

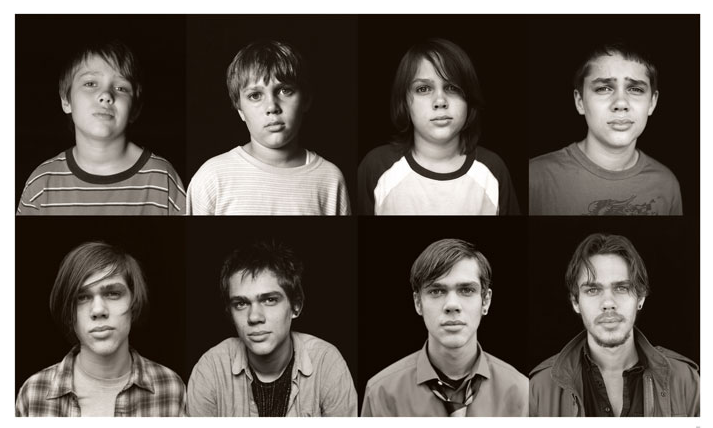

Obviously, we see Mason (Ellar Coltrane) throughout his life with each scene as a snapshot of his life in a year. Linklater had to get creative in his editing techniques, as for the film's unconventional filming. The abrupt transition between each scene may seem messy or unnatural to the average viewer, yet isn't this the same way we grow up? Through each year, especially the young teenage years, we grow and we change the person we are, whether it's aesthetically (as Mason does) or thoughtfully. One transition that embodies this is from middle into high school, where Mason was just drinking with some less-than-cool high school boys as a 13 year old, and directly after, the scene cuts to a year later, where Mason now has a girlfriend and is smoking weed. In the scenes before, when Mason is still very young, we hardly saw him experiment, but this is pivotal, as this can be the age an average American kid will begin to engage in these activities. Yet, this seemingly awkward transition, in which Mason's hair has grown some considerable inches, we see a growth in his demeanor, more cool and understanding.

Obviously, we see Mason (Ellar Coltrane) throughout his life with each scene as a snapshot of his life in a year. Linklater had to get creative in his editing techniques, as for the film's unconventional filming. The abrupt transition between each scene may seem messy or unnatural to the average viewer, yet isn't this the same way we grow up? Through each year, especially the young teenage years, we grow and we change the person we are, whether it's aesthetically (as Mason does) or thoughtfully. One transition that embodies this is from middle into high school, where Mason was just drinking with some less-than-cool high school boys as a 13 year old, and directly after, the scene cuts to a year later, where Mason now has a girlfriend and is smoking weed. In the scenes before, when Mason is still very young, we hardly saw him experiment, but this is pivotal, as this can be the age an average American kid will begin to engage in these activities. Yet, this seemingly awkward transition, in which Mason's hair has grown some considerable inches, we see a growth in his demeanor, more cool and understanding.

Another scene where Linklater's interesting approach at editing is when directly after Mason's mother, Olivia (Patricia Arquette), exclaims that she thought there would be more to her own life, Mason's interaction with the girl he meets at his college leaves many viewers confused and without closure. Just as we think to a film as long and almost uneventful as this must have a super-thrilling ending, it's a simple stoner-esque, brief thought to end this epic. Just as life itself, whether it is high school graduation, or moving out for the first time, or meeting our first friends in college, we always expect more, just as Mason's mom has, and we do at the end of this film. It seems a bit of a cop-out or a simple ending to an epic of a movie, but this adds much needed closure to the film's mission to convey a full and true life.

Yet, while viewing the film, there are no instances of editing that scream out to me as "bad", one in particular seems somewhat awkward and not in the good, thematic way as above. After Mason and his girlfriend Sheena visit his sister at college, they undergo a serious and painful breakup. While this can showcase how a high school relationship can go from sweet to sour in the matter of minutes (or scene cuts), it seemed rushed and awkward while watching. They were just beatific in bed together, and suddenly and without any actual indication, Sheena has slept with another guy. Both Mason and Sheena act childish in their breakup, and after this, we no longer see Sheena, as high school breakups usually end.

Yet, while viewing the film, there are no instances of editing that scream out to me as "bad", one in particular seems somewhat awkward and not in the good, thematic way as above. After Mason and his girlfriend Sheena visit his sister at college, they undergo a serious and painful breakup. While this can showcase how a high school relationship can go from sweet to sour in the matter of minutes (or scene cuts), it seemed rushed and awkward while watching. They were just beatific in bed together, and suddenly and without any actual indication, Sheena has slept with another guy. Both Mason and Sheena act childish in their breakup, and after this, we no longer see Sheena, as high school breakups usually end.

It isn't easy comparing this film's means of editing to any other, given this may be the most commercially successful film that was filmed over an extended period of time. While Boyhood's extended time was intentional, one can compare the film's abrupt cuts and themes of realism to Alexander Payne's Nebraska. Both film's convey a sense of realism to the viewer through the means of simple and abrupt editing. For both Nebraska and Boyhood, we want more out of the film, like the finale, where everything comes in full circle and the abrasive, alcoholic, old man gets the prize movie he's been searching for, and Mason comes to some conclusion about his existence, yet we don't get that. Instead, the realism sets in, and we understand the themes of this film are abrupt and unpredictable, just as life is.